Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Goats

| PDF |

ISBN 978-1-988793-43-6 (book)

ISBN 978-1-988793-42-9 (electronic book text)

Available from:

Canadian National Goat Federation

P.O. Box 61, Annaheim SK S0K 0G0 CANADA

Website: www.cangoats.com

Email: info@cangoats.com

For information on the Code of Practice development process contact:

National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC)

Email: nfacc@xplornet.com

Website: www.nfacc.ca

Also available in French

© Copyright is jointly held by the Canadian National Goat Federation and the National Farm Animal Care Council (2022)

This publication may be reproduced for personal or internal use provided that its source is fully acknowledged. However, multiple copy reproduction of this publication in whole or in part for any purpose (including but not limited to resale or redistribution) requires the kind permission of the National Farm Animal Care Council (see www.nfacc.ca for contact information).

Acknowledgment

|

|

Funded in part by the Government of Canada under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s AgriAssurance Program, a federal, provincial, territorial initiative.

Disclaimer

Information contained in this publication is subject to periodic review in light of changing practices, government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/or without seeking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the authors shall not be held responsible for loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Furthermore, the authors expressly disclaim all and any liability to any person, whether the purchaser of the publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, by any such person in reliance on the contents of this publication.

Cover image photo credits: top photo: Catherine Michaud; second to top photo: Melissa Moggy*; second from bottom: Theresa Bergeron; bottom photo: Robin Schill.

*Please note that that photo was taken on the farm of Code Development Committee producer Jean-Philippe Jolin. He, along with all others, have provided their permission to use in the Goat Code.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Appendices: | ||

| Appendix A | - Sample Goat Welfare Policy | |

| Appendix B | - Emergency Telephone List | |

| Appendix C | - Mapping Barns and Surrounding Areas for Fire Services | |

| Appendix D | - Assessing Farm Buildings for Fire Prevention | |

| Appendix E | - To Prepare in Case of Evacuation | |

| Appendix F | - Body Condition Scoring | |

| Appendix G | - Goat Flight Zone | |

| Appendix H | - Properly Trimmed and Overgrown Hooves | |

| Appendix I | - Hair Problems around Genitals | |

| Appendix J | - Example of Decision Tree for Euthanasia | |

| Appendix K | - Lameness Scoring | |

| Appendix L | - Important and Serious Infectious Diseases of Goats: Signs and Causes | |

| Appendix M | - Transport Decision Tree | |

| Appendix N | - Anatomical Landmarks for Euthanasia | |

| Appendix O | - Secondary Steps to Cause Death | |

| Appendix P | - Sample On-Farm Euthanasia Action Plan | |

| Appendix Q | - Acceptable Calibres and Cartridges for Euthanasia of Goats | |

| Appendix R | - Standards for Optimizing Animal Welfare Outcomes during Slaughter without Stunning | |

| Appendix S | - Resources for Further Information | |

| Appendix T | - Participants | |

| Appendix U | - Summary of Code Requirements | |

Preface

The National Farm Animal Care Council (NFACC) Code development process was followed in the development of this Code of Practice. The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Goats replaces its predecessor developed in 2003 and published by the Canadian Agri-Food Research Council (CARC).

The Codes of Practice are nationally developed guidelines for the care and handling of farm animals. They serve as our national understanding of animal care requirements and recommended practices. Codes promote sound management and welfare practices for housing, care, transportation, and other animal husbandry practices.

Codes of Practice have been developed for virtually all farmed animal species in Canada. NFACC’s website provides access to all currently available Codes (www.nfacc.ca).

The NFACC Code development process aims to:

- link Codes with science

- ensure transparency in the process

- include broad representation from stakeholders

- contribute to improvements in farm animal care

- identify research priorities and encourage work in these priority areas

- write clearly to ensure ease of reading, understanding and implementation

- provide a document that is useful for all stakeholders.

The Codes of Practice are the result of a rigorous Code development process, taking into account the best science available for each species, compiled through an independent peer-reviewed process, along with stakeholder input. The Code development process also takes into account the practical requirements for each species necessary to promote consistent application across Canada and ensure uptake by stakeholders resulting in beneficial animal outcomes. Given their broad use by numerous parties in Canada today, it is important for all to understand how they are intended to be interpreted.

Requirements – These refer to either a regulatory requirement or an industry-imposed expectation outlining acceptable and unacceptable practices and are fundamental obligations relating to the care of animals. Requirements represent a consensus position that these measures, at minimum, are to be implemented by all persons responsible for farm animal care. When included as part of an assessment program, those who fail to implement Requirements may be compelled by industry associations to undertake corrective measures or risk a loss of market options. Requirements also may be enforceable under federal and provincial regulations.

Recommended Practices – Code Recommended Practices may complement a Code’s Requirements, promote producer education, and encourage adoption of practices for continual improvement in animal welfare outcomes. Recommended Practices are those that are generally expected to enhance animal welfare outcomes, but failure to implement them does not imply that acceptable standards of animal care are not met.

Broad representation and expertise on each Code Development Committee ensures collaborative Code development. Stakeholder commitment is key to ensure quality animal care standards are established and implemented.

This Code represents a consensus amongst diverse stakeholder groups. Consensus results in a decision that everyone agrees advances animal welfare but does not necessarily imply unanimous endorsement of every aspect of the Code. Codes play a central role in Canada’s farm animal welfare system as part of a process of continual improvement. As a result, they need to be reviewed and updated regularly. Codes should be reviewed at least every 5 years following publication and updated at least every 10 years.

A key feature of NFACC’s Code development process is the Scientific Committee. It is widely accepted that animal welfare codes, guidelines, standards, or legislation should take advantage of the best available research. A Scientific Committee review of priority animal welfare issues for the species being addressed provided valuable information to the Code Development Committee in developing this Code of Practice.

The Scientific Committee report is peer reviewed and publicly available, enhancing the transparency and credibility of the Code.

The Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Goats: Review of Scientific Research on Priority Issues developed by the Goat Code of Practice Scientific Committee is available on NFACC’s website (www.nfacc.ca).

Introduction

While domestic goats are not native to Canada, they have proven to be extremely adaptable to our diverse resources, climate, and geography. In this relatively young and growing sector of agriculture, the central focus of the Canadian goat industry is production of milk, meat, and fibre managed under a variety of housing and grazing systems.

Ontario and Quebec are the main producers of goat products in Canada. Goat milk is mainly made into cheese with a lesser amount being processed into yogurt, ice cream, fluid milk, butterfat, and powdered milk. Goat milk production is a small proportion of total milk production in Canada; however, there has been substantial growth in the number of animals, farms, and total milk produced. In Canada, the number of meat and dairy goats has increased from 230,034 goats reported in the 2016 Census to 253,278 goats on 4,801 Canadian farms in 2021 (20, 21). New Canadians also continue to support their cultural traditions and food preferences which often include goat meat. To meet this demand, the availability of goat meat in larger cities is increasing.

Due to their naturally curious and interactive nature, goats are also commonly featured in agri-tourism and unique small businesses such as pack animals, targeted grazers, exercise companions, petting zoos, and entertainment. They are also commonly kept as companion animals, pets, or in small hobby herds. Regardless of their purpose, the same principles of responsible care and management must be practiced across the industry to safeguard the well-being of goats.

An animal is in a good state of welfare if (as indicated by scientific evidence) it is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, able to express innate behaviour, and if it is not suffering from unpleasant states such as pain, fear, and distress (11).

Codes of Practice strive to promote standards of care that reflect achievable balances between animal welfare and producer capabilities. This Code updates the 2003 goat Code of Practice. It attempts to reflect both modern and traditional management practices while seeking to advance animal welfare as described by NFACC.

Appropriate husbandry, handling, and management are essential for the health and well-being of goats. The care and management provided by the person(s) responsible for daily care has a significant influence on their welfare. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of producers to ensure that all personnel can perform their duties properly. This Code of Practice provides guidance to owners and their families, as well as employees, for the welfare of goats in their care.

The Code identifies welfare hazards, opportunities, and methods to promote well-being. Key knowledge required includes an understanding of the basic needs and behaviour of goats, along with farm protocols and processes. Producers should strive to maintain content, productive, and healthy animals through good management practices by striving to:

- ensure that housing (including natural shelter) and handling systems provide shelter and protection from extreme weather, adequate space and good air quality, allow safe movement of goats, and accommodate natural behaviours

- ensure that goats receive sufficient quantities of feed and water to maintain good health and body condition and to minimize nutrition-related diseases

- improve animal well-being through proactive disease prevention and monitoring herd health, while providing prompt, appropriate treatments

- safeguard goat welfare by minimizing threats from barn fires, power or mechanical failures, extreme weather, and natural disasters

- ensure, through proper preparation, that goats being transported experience the least possible stress without pain and unnecessary suffering and arrive at their destination in good health and condition

- ensure that goats are euthanized or slaughtered promptly and with minimal pain and distress.

This Code does not cover all production and management practices relevant to each sector of goat production. Instead, principles applicable to all sectors of the industry are presented, along with some sector-specific considerations.

The goat Code includes important pre-transport considerations but does not address animal care during transport. Please consult the current Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals: Transportation for information on animal care during transport (22).

Anyone building new or modifying or assuming management of existing goat facilities will need to be familiar with local, provincial, and federal requirements for construction, environmental management, and other areas outside the scope of this document. Individuals requiring further details should refer to local sources of information such as universities, agricultural ministries, and industry resources (refer to Appendix S – Resources for Further Information).

The Requirements in the Code may be enforced by various authorities (e.g., welfare agencies or governments) and can be used to legally define accepted standards of care in most provinces and territories. Provincial and Federal legislation are also applicable to livestock production (e.g., Health of Animals Act and its Regulations).

It is of benefit to the entire Canadian goat industry that the community of goat producers assures goat husbandry is of the highest standard possible.

Glossary

Alternative medicines/therapies: defined as existing separately from and as a replacement for conventional veterinary medicine. The safety and efficacy of these alternative therapies should be demonstrated by scientific methods and evidence-based principles and should be provided within the context of a valid veterinary-client-patient relationship (1).

Analgesia: to control or reduce pain usually through the administration of a local anaesthetic or the use of a systemic medication such as a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID).

Analgesic: a drug that relieves pain.

Anemia: a condition in which the blood is deficient of healthy red blood cells (2).

Artificially-raised: when kids are removed from the dam or orphaned/rejected and fed milk or milk replacer by stockpeople until they are weaned. Also known as “hand-reared.”

Assembly centre: for the purposes of Part XII of the Health of Animals Regulations, referring to a place where animals are transported for the purposes of assembly (includes auction markets, assembly yards, and holding facilities other than slaughter establishments; 3).

Barbiturate: an injectable anaesthetic and controlled drug that, when given in a high concentration, can be used by a veterinarian to perform euthanasia.

Bedded pack: bedding that consists of a selected bedding material being gradually added and mixed with animal manure (4).

Buck: adult male goat.

Buckling: a young male goat, usually less than 1 year of age.

Canadian Standards Association (CSA): a provider of product testing and certification services for electrical, mechanical, plumbing, gas, and other products (5).

Caprine Arthritis Encephalitis (CAE): a virus that infects goats for life. Infected animals usually do not develop clinical signs of disease until approximately 3 years of age. Signs can include chronic arthritis, bursitis, and reduced milk production.

Caseous Lymphadenitis (CLA, CL): a highly contagious bacterial disease transmitted by contact with contaminated goats, feed, bedding, stockpeople, or equipment. Characterized by abscesses in lymph nodes and sometimes internal organs.

Cashmere: soft downy winter hairusually gathered by combing. May be obtained from Cashmere goats bred specifically for cashmere production or in very small quantities from other breeds of goats.

Claiming pen: a pen where does and their newborn kids are kept to facilitate bonding. Also known as the bonding pen.

Cold stress: when goats are exposed to temperatures below their thermoneutral zone and they expend energy to keep warm. Cold stress can lead to severe hypothermia (rectal temperature < 37o C).

Comb lifter: a plate, fitted to the bottom of a shearing comb, to leave an insulating cover of mohair on the Angora goat when shearing.

Competent person: a person whodemonstrates skill and/or knowledge regarding a particular topic, practice, or procedure that has been developed through training, education, experience, and/or mentorship.

Compromised animal: an animal with reduced capacity to withstand the stress of transport due to injury, fatigue, infirmity, poor health, distress, very young or old age, impending birth, peak lactation, or any other cause. Special provisions must be taken for transporting these animals (3).

Conjunctiva: mucousmembrane that lines the orbit of the eye and eyelid.

Consciousness: a state of awareness, able to feel pain and/or to respond to touch, sound, and/or sight.

Container: a box or crate designed, constructed, equipped, and maintained for the shipment of animals, suitable for the species (i.e., allows the animal to stand upright with all feet on the ground in preferred position, with full range of head movement, without touching any part of its body to the roof, top, or covering; is well ventilated; and is used in a manner that is not likely to cause injury, suffering, or death). Must also allow the animal to lie down and get up with ease and comfort. Can be moved independently from one mode of transportation to another (3).

Conveyance: any vehicle or container used to move animals or things. For example, conveyance can include aircraft, carriage, motor vehicle, trailer, railway car, vessel, and other means of transportation, including cargo containers (6).

Corneal reflex: involuntary blinking in response to touching the cornea (front of the eyeball).

Crook: a shepherd's staff with one end curved into a blunt hook, used to catch or restrain animals by the neck or leg.

Crutching: the removal of hair or mohair (Angora) from around the tail, flank, udder, perineum, and inner legs of the goat for the purposes of hygiene (e.g., kidding and suckling of newborn kids).

Dam-raised: a kid that is left to suckle on its mother until weaned.

Dehorning: the process of removing horn tissue after the horn bud attaches to the skull (7, 8).

Dewattling: removal of wattles (see “Wattles”).

Disbudding: a procedure that removes the horn bud (from which the horn grows) before it attaches to the skull (7, 8).

Disease: a disorder of structure or function of the body, especially one that produces specific signs of illness (e.g., fever, poorer growth) and is not simply a direct result of physical injury.

Doe: adult female goat.

Doeling: a young female goat, usually less than one year of age.

Dried-off: cessation of milking either with or without tapering-off. The udder ceases to produce milk until the doe gives birth again.

Drug Identification Number (DIN): an eight-digit number assigned by Health Canada that identifies a drug product that has been evaluated and approved for sale in Canada (9).

Dysentery: a gastrointestinal infection (usually due to a viral, bacterial, or parasitic infection) that causes abdominal pain and straining diarrhea containing blood or mucus (10).

Electroejaculation: the retrieval of semen by electrical stimulation of the prostate using an electroejaculator device.

Euthanasia: ending the life of an individual animal for humane reasons in a way that minimizes or eliminates pain and distress (11).

Exsanguination: removal of blood from the animal to the point of death.

Extra-Label Drug Use (ELDU): using a drug in any manner not indicated on the label.

Failure of passive transfer of immunity (FPT): when a newborn animal has not received adequate passive immunity (i.e., immunoglobulins) from the colostrum consumed. It may be because the level of immunoglobulins provided was inadequate or that the animal was unable to adequately absorb the immunoglobulins provided.

Fire break: a natural or constructed barrier used to stop or check fires that may occur or to provide a control line from which to work.

Fly strike: a painful condition which occurs when the eggs of blowflies are laid and hatch in a wound or in moist or manure-stained hair, and the maggots burrow and feed on the flesh of the live animal (12).

Foot scald: a bacterial infection between the claws of the foot (i.e., toes). The skin is reddened, swollen, and sensitive to touch, and the goat is lame. Often caused by wet, dirty, or muddy conditions (13).

Foot rot: disease of the foot caused by a bacterial infection (Dichelobacter nododus). It can cause painful erosion of tissue between the sole of the toe and outer hoof, resulting in severe lameness. Pus and a foul smell may also be present. It can be spread between goats by contaminated pasture, housing, and foot-trimming equipment (13).

Foremilk: the first stream of milk from the teat.

Free choice (ad libitum): unlimited access. Usually refers to feed and water.

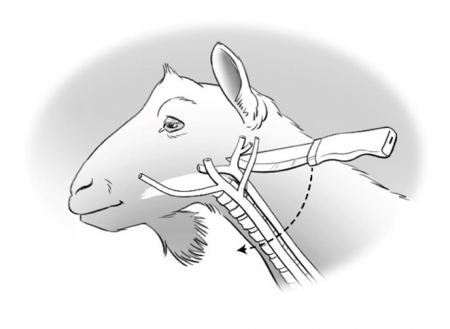

Headstall: a stand that is constructed to hold a goat.

Heat stress: when goats are exposed to temperatures above their thermoneutral zone andmust use more energy to maintain normal body temperature. Heat stress can lead to hyperthermia (rectal temperature > 41°C).

Immunoglobulins: antibodies produced by immune cells in the animal’s body. Usually in response to infection with viruses, bacteria, or parasites; also produced in response to vaccination. The purpose of the antibodies is to fight the infectious agents.

Isolate: to keep an animal apart from other animals for the purpose of preventing contact. The reasons for isolation are many and include to prevent transmission of disease agents and to prevent injury or suffering.

Joint ill: a bacterial infection of the joints, usually of youngstock. The joints most often affected are the knees (carpus), stifles, and hocks. One or more joints may be involved.

Johne’s disease: a fatal bacterial gastrointestinal disease of goats and other ruminants (including cattle, sheep, elk, deer, and bison) that presents as severe weight loss in animals usually > 2 years of age. Also known as paratuberculosis, the bacteria are shed in the manure and sometimes milk for months before the animal appears ill and are very hardy to the environment (14).

Kid: a young goat (usually less than one year of age).

Limit feeding: limiting the amount of feed that is available over a set period of time; the goats may not necessarily eat to satiation (to appetite).

Livestock guardian animal: an animal used to protect livestock from predators. Commonly include certain breeds of dogs, as well as llamas and donkeys.

Loading density: the amount of space given to each animal per unit of space on a conveyance. It should be proportional to the animal's size, its condition, and the weather conditions (temperature and humidity) at the time of transport (3).

Local anesthetic: an anaesthetic drug that induces a loss of feeling or sensation in an area.

Low stress handling: handling goats in a quiet, calm, and controlled manner utilizing their natural herd instincts and behaviours to minimize stress and the risk of injury to the animal(s) and stockpeople.

Marking harness: a harness used with bucks consisting of a coloured crayon on the area of the buck’s brisket that marks does that have been mounted.

Mastitis: inflammation of the udder, usually due to an infectious agent. It may be clinical (e.g., the udder is swollen and hot, the milk discoloured) or subclinical (milk appears normal but milk production is decreased).

Medically Important Antimicrobials – Category I: Antimicrobials that are of very high importance in human medicine (e.g., carbapenums and fluroquinolones) and there are limited or no alternatives for these antimicrobials (15).

Medically Important Antimicrobials – Category II: Antimicrobials that are of high importance in human medicine (e.g., macrolides and penicillins) and alternative antimicrobials for these antimicrobials are generally available (15).

Medically Important Antimicrobials – Category III: Antimicrobials that are of medium importance in human medicine (e.g., sulphonamides and tetracyclines) and alternative antimicrobials for these antimicrobials are generally available (15).

Milk vein: a large subcutaneous vein that extends along each side of the lower abdomen of the goat and returns blood from the udder.

Mohair: fibre sheared from the Angora goat.

Moribund: an animal very near death; death is imminent.

Natural shelter: landscape features that form shelters. May include valleys, lee sides of hills, and bush areas. May provide shade, a cool place to lay, or wind protection.

NEMA 4X: a National Electrical Manufacturers Association rating for an outdoor electrical enclosure that incudes:

- protection against liquid and solid ingress

- resistance to corrosion

- protection against damage from ice forming on the outside of the enclosure (16).

Non-ambulatory animal: an animal that is unable or unwilling to stand or move forward without assistance. Non-ambulatory animals may also be called "downers."

Nursery-raised: See “artificially-raised.”

Passive immunity: immunization of kids from the passing of immunoglobulins from colostrum consumed. Protection usually lasts 4 to 6 weeks(10).

Pathogen: an agent (e.g., bacteria, virus, parasite) that can infect an animal and cause disease.

Perioperative analgesia: a drug administered before, during, and/or shortly after a procedure to control or reduce pain.

Photoperiod: the period of time each day during which goats receive light of a sufficient strength to mimic daylight.

Pithing: the process of destroying the brain tissue of an unconscious animal to prevent a return to consciousness and to assure death. Pithing is performed by inserting a rod through the hole in the skull created by a penetrating captive bolt device.

Pizzle: another term for penis.

Pizzle rot: infection and inflammation of the foreskin caused by feeding a diet high in soluble proteins or because conditions cause the area to become favourable to bacterial growth (e.g., mohair matting). May lead to fly strike, scarring of the preputial opening, or urine retention. Also known as “infectious balanoposthitis.”

Prepubescent: the period preceding puberty (i.e., sexual maturity). Puberty may be reached as young as 3 months of age for a buckling and 5 months of age for a doeling.

Queuing: One or more goats waiting in order to access a resource, such as feed or water that is occupied by another goat.

Ritual slaughter: the practice of slaughtering livestock for meat in the context of a ritual (i.e., for Judaic or Islamic law).

Scurs: a deformed horn resulting from damage to the horn bud; damage may be from injury or poor disbudding technique.

Shorn/Sheared: animals whose hair coat has recently been trimmed or clipped close to the skin, using either special hand or electric clippers designed for this purpose.

Stanchion: a set of adjustable, upright partitions that close around a goat's neck, so that the goat can be temporarily held (e.g., for milking and feeding).

Stillbirth: a kid born dead at term or dying very soon after birth as a result of the birth process.

Strip cup: a special-purpose cup with a dark solid-surfaced or fine-mesh lid. The foremilk is squirted onto the lid to detect abnormalities such as clots, discoloured or watery milk that may indicate mastitis (17).

Stocking density: the number of animals on a particular piece of land at a particular point in time (18).

Stunning: rendering an animal unconscious.

Sub-acute ruminal acidosis (SARA): an abnormally low ruminal pH (i.e., acidic). Occurs when goats have an unbalanced ration consisting of rapidly fermentable carbohydrate source (e.g., grain, pellets). May worsen if the diet contains insufficient effective fibre. Can cause chronic damage to the wall of the rumen and is an important risk factor for laminitis (19).

Tail web: a web of skin on either side of the base of the tail.

Top dress: when grain, mineral, or other supplement is added on top of another feed and offered to the animal without mixing.

Unconsciousness: insensible; unable to feel pain and to respond to touch, sound, and sight. Contrast with “consciousness” (10).

Underwriters Laboratories of Canada (ULC): an independent product safety testing, certification, and inspection organization – www.canada.ul.com.

Unfit animal: an animal that is sick, injured, disabled, or fatigued and that cannot be moved without causing additional suffering. These animals must not be transported unless under the recommendation of a veterinarian for veterinary care (with measures taken to prevent additional suffering; 3).

Urinary calculi: solid particles that form in the bladder when dietary conditions allow. In male goats, these stones may become lodged in the urethra and slow or prevent urination. Also known as “urolithiasis.”

Wasting: a serious loss of body weight (10).

Wattles: dangling appendages under the throat or along the neck of goats that serve no apparent purpose but contain blood, nerves, and cartilage.

Weaning: the practice of removing kids from the milk diet provided by the doe or a milk replacement diet (12).

Weaning stress: the stress associated with weaning that may result in slower growth or weight loss. Also known as “weaning shock.”

Wether: a castrated male goat.

Wool blindness: when excessive mohair growth near the eyes interferes with normal sight.

1. Roles and Responsibilities

Producers and managers have a primary responsibility for ensuring that goat health and welfare are a priority on the farm. Before stockpeople are assigned their duties, they need to be knowledgeable of the basic needs of, and skilled in caring for, goats in all stages of production. While managers have a primary responsibility for ensuring personnel are trained, all those involved in animal care should be encouraged to identify areas where they would benefit from additional training.

REQUIREMENTSPersonnel working with goats must have ready access to a copy of this Code of Practice, and be familiar with, and comply with, the Requirements as stated in this Code. Producers must ensure that personnel involved in the care and management of goats are knowledgeable, skilled, trained, competent, and supervised. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- develop and implement a written Goat Welfare Policy outlining the farm’s commitment to responsible and humane animal care (refer to Appendix A – Sample Goat Welfare Policy)

- identify supervisors or managers that personnel can approach with questions or concerns about animal care.

2. Housing and Handling Facilities

Desired Outcome: ensure that housing (including natural shelter) and handling systems provide shelter and protection from extreme weather, adequate space and good air quality, allow safe movement of goats, and accommodate natural behaviours.

Goats may be raised indoors in loose housing, group pens, or with partial/full access to outdoor dry lots, yards, or pastures with night pens or shelters. They may also be raised exclusively outdoors with natural or manufactured shelter. Goats are highly adaptable to the various climates in Canada; however, they do require shelter from wind, rain, and extreme cold weather as well as protection from extreme heat. Goats tend to seek shelter or hide overnight, during adverse weather, when there is a risk of predators, and/or to escape aggressive behaviour (23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

Does kidding in winter or extreme cold and does raising nursing kids need a facility with maternity pens for kidding and early care to promote kid survival.

Natural landscape features are acceptable forms of shelter. Valleys, lee sides of hills, and bush areas can provide shade, a cool place to lay, and some protection from wind. Properly designed windbreaks and hedgerows can also provide additional protection from wind chill. It is critical that an adequate manufactured shelter is available to goats if natural landscape shelter or windbreaks do not provide sufficient protection from extreme weather. Monitoring behaviour, body condition, and goat health will support decision-making to build or use manufactured shelter.

REQUIREMENTSGoats must have access to shelter. Goat shelters or buildings, either natural or manufactured, must mitigate the harmful effects of rain, wind, and extreme cold and heat. Goat housing, including shelters, must keep goats clean and dry. Building materials with which goats come into contact must not contain harmful compounds. |

2.1 Building Environment

2.1.1 Temperature

While goats tolerate hot and cold temperatures, they should be protected from large fluctuations in temperature, drafts, and wind chill.

Clean dry bedding will assist goats in being comfortable in cold weather. Shelter from snow and rain allow goats’ coats to remain dry and to provide maximum insulating value. The comfort zone for goats is between 10 and 20°C (50 to 68°F), but this will vary based on factors such as age and coat length. Temperatures over 26°C (80°F), however, seriously reduce feed intake and milk output (28).

Goats need higher energy in their diet to maintain body temperature and body condition during extreme cold. Signs of cold stress include shivering, huddling, grinding teeth, increased feed intake, and seeking shelter if available.

Newborn kids quickly use up their fat stores when born into a cold environment, especially if the kids are wet, and are at risk of starvation and chilling. Along with adequate colostrum, it is important to provide a warm, draft-free area for newborns and very young kids (e.g., supplemental heat, small shelter, or deep bedding) to prevent hypothermia (chilling) and starvation (29).

Goats experiencing heat stress may have increased respiration rates, panting, shallow breathing, reduced lying time, and increased shade seeking. Heat stress also lowers natural immunity, making animals more vulnerable to disease in the following days and weeks (30).

REQUIREMENTSFor the first week of life kids must be protected from wind chills and drafty, cold conditions. Stockpeople must be able to recognize and promptly assist goats displaying signs of heat or |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- maintain kid-rearing areas at temperatures that keep kids in their comfort zones (i.e., no signs of heat or cold stress)

- check heating systems regularly to ensure that they are safe and in good working order (31)

- plan breeding to avoid winter kidding if housing and/or management cannot keep kids warm

- mitigate cold stress using these steps (11):

- increase the ambient temperature in heated barns

- provide insulated and/or heated flooring

- protect goats from wind and moisture (e.g., wind break, three-sided shelters facing south) with the addition of a screen for wind protection

- provide straw bedding (which offers more insulation than other bedding types) and ensure that the depth permits goats to nest (legs are covered when laying down)

- adjust the feeding program to meet increased energy demands

- prevent condensation by assuring adequate ventilation

- provide goats with clean and dry goat coats or calf coats

- mitigate heat stress using these steps (11):

- provide shade through natural or artificial means (e.g., shade cloths, trees)

- provide ample cool, clean water

- avoid handling or other stressors especially during the hottest times of the day

- increase air flow: open vents (i.e., windows, curtains), add more fans to indoor housing.

2.1.2 Ventilation and Air Quality

Proper ventilation is critical to maintaining good air quality and a good barn environment for goats. Pneumonia, hypothermia, and cold stress all contribute to kid mortality and can be minimized with properly ventilated buildings (12).

Air quality is affected by humidity, dust, odours, and the accumulation of gases such as ammonia. Decomposition of feces and urine produces ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, methane gas, and other odours (33).

The ventilation system, whether natural or mechanical, should (21):

- provide adequate fresh air at all times

- distribute fresh air uniformly without causing drafts

- exhaust the respired moisture

- remove odours and gases, such as ammonia (34).

Humidity levels vary depending on weather conditions, stocking density, bedding management, and goat diet. Air circulation that reaches the manure pack reduces buildup of humidity. Excess moisture from wet bedding and expired air will condense on cold surfaces (e.g., ceilings, exterior walls, and steel beams), adversely affect air quality, and settle on the goats, which will lower the ability of the animals to withstand cold stress.

Manure gases can increase the risk of respiratory infections by interfering with the immune system of the lung, in particular its ability to clear pathogens such as viruses and bacteria. Manure gases are heavier than air and so are in higher concentrations closer to the ground, thus putting younger/smaller goats at higher risk of their adverse effects (35).

Ammonia is recognized as an irritant to goats’ eyes and respiratory tract and can pose a health threat not only to goats but also to the people that work with them. Sheep (and possibly goats) exposed to ammonia levels of 21 mg/m3 or higher may reduce feed intake and weight gain (36). A maximum ammonia concentration of 25 ppm corresponds to safety standards established for humans for continuous 8-hour exposure but is not necessarily pleasant for humans or animals (37, 38). The smell of ammonia generally becomes aversive to humans at a concentration of 17 ppm (39). Once aversive, steps should be taken to establish a comfortable environment for goats and personnel (e.g., opening windows or doors).

Providing sufficient fresh air to lower ammonia without causing cold drafts may involve increased monitoring of the environment, installing additional equipment, renovating building(s), and adjusting settings on windows, doors, chimney baffles, curtains, and ventilation fans.

Properly designed ventilation is a critical component to housing design and will contribute to animal, as well as worker, health and safety by assuring good air quality. Improved air quality reduces incidence of respiratory illnesses and promotes better welfare for goats and humans within the barn environment.

REQUIREMENTSGoat housing must have ventilation (natural or mechanical) to bring in fresh air and exhaust humidity and manure gases. Condensation visible on surfaces or in the air requires corrective action. Corrective actions must be taken if ammonia is either detected by smell or if levels are more than 25 ppm. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- establish a protocol or written standard operating procedure (SOP) for inspecting and maintaining ventilation systems

- ensure that stockpeople are able to recognize the physical human response to high manure gases levels when entering barns (e.g., odour, irritation of the eyes [tearing], nose, and lungs)

- remove manure as required to maintain good air quality

- add more bedding to manure packs to reduce ammonia release

- measure ammonia levels using an instrument or test kit to determine levels

- consult an agricultural engineer to help solve ventilation issues

- adjust ventilation rate and/or lower the stocking density in hot weather

- eliminate cold drafts at animal level and/or add a safe supplementary heater, if necessary, in cold weather

- maintain good air quality through sufficient air exchange regardless of weather conditions and outside temperatures

- use an electrician and/or a professional during ventilation installation to avoid fire hazards.

2.1.3 Lighting

Goats are seasonal breeding animals that are sensitive to photoperiod.

Light is required for proper observation, care of the herd, and goats’ activities during the day. Lighting can be controlled or artificially manipulated, depending on breeding management needs. An appropriate period of rest from artificial lighting (e.g., 6 hours) allows goats to maintain their natural photoperiod.

REQUIREMENTSGoats must have sufficient light to facilitate care and observation. Artificial lighting must be added to buildings with low natural light. An appropriate period of rest from artificial lighting (at a minimum, 6 hours) must be provided to allow goats to maintain their natural photoperiod. All electric wires and fittings must be well out of reach of goats and well protected (29). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- window area should equal a minimum of 5% (1/20) of ground surface area (22)

- clean windows to maximize light entry.

2.2 Building Features

2.2.1 Pen Design

Penning should be effective, comfortable, safe, durable, and permit the observation of all animals. Pens should also provide room for rest and exercise. Pen sizes should allow for kidding, treating sick animals, isolation, and husbandry procedures, as well as low-stress movement within a facility. Hospital pens should allow more space per goat for resting, feeding, and drinking.

Pen and alley design should consider common goat behaviours such as:

- goats are naturally playful with a propensity to climb, jump, and escape

- goats are curious. Horns, heads, and feet can get trapped in small openings

- goats like to stand with front feet elevated on horizontal gates, penning, fences, and equipment

- goats want to see where they are going

- goats prefer to be near their herd and are stressed when alone.

REQUIREMENTSFences, gates, penning, and feeders must be designed to prevent accidental entrapment. All penning must be maintained and repaired or replaced as needed. Barriers, pen dividers, or other penning or handling structures must have no sharp edges or protrusions that might injure goats (32). Pens must be available to separate and treat goats. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- consider natural goat behaviours in animal flow designs to minimize stress

- note repeated injuries or mortalities when handling animals, and determine causes to prevent future injuries

- locate hospital and maternity pens apart from one another

- provide safe options for goats to climb, such as raised platforms (40, 41).

2.2.2 Floor Space Allowance in Pens

The amount of space needed per goat varies greatly depending on breed, age, size, presence of horns, feeding, reproductive stage, temperature, environment, production style, and pen management. For example, the space needed for a pregnant doe with horns may double in the last month of gestation as size increases and the doe becomes more irritable, especially in hot weather.

Overcrowding is stressful for goats and can lead to fighting as goats try to establish social dominance. At higher stocking densities, lower-ranking goats will spend less time at feeders and less time laying down resting.

It is important to observe goats for negative behaviours such as:

- clashing and butting

- pushing and displacing

- threatening (or bullying)

- nipping and biting

- dirty hair (from goats climbing over each other to access feed)

- noticeable queuing (lining up) at feeder(s) or waterer(s)

- decreased feed intake, lost body condition (particularly among goats of lower social ranking).

Providing raised platforms in goat housing is an effective way to increase space allowance without increasing the dimensions of a pen, while allowing goats to perform their natural behaviours of climbing and hiding. Multiple levels may also reduce aggressive behaviours between goats (42).

Some minimum space allowance guidelines are reflected in Table 2.1. Less than 1.5 m2 of space is considered to adversely affect an adult goat’s welfare (43). The goal in all cases is to provide every goat with enough space to perform their normal behaviours (e.g., eating, sleeping). It is critical that stockpeople observe goats for overcrowding behaviours (i.e., indicating a need for more space per goat).

Exceeding minimum floor space guidelines will likely decrease fighting and stress and benefit goat health and welfare.

Table 2.1 – Minimum Floor Space per Goat for Different Physiological Stages

Goat Physiological Stage | Pen Space per Goat – Minimum area to provide* | |

m2 / head | ft2 / head | |

Pre-weaned Kids | 0.6 | 6.5 |

Weaned Kids (e.g., 8 weeks or older) | 0.9 | 10 |

Mature Does | 1.5 | 16 |

Mature Bucks | 2.8 | 30 |

Nursing Does | 1.5/doe + 0.6/kid | 16/doe + 6.5/kid |

Kidding Pens | 2 | 22 |

Hospital Pens | 2.5 | 27 |

*Minimum floor space is dependent on breed, age, size, presence of horns, feeding, reproductive stage, temperature, environment, production style, and pen management. Increase space allowance by 10% when in full fleece, 17% for horned goats, and 25% for pregnant does. Smaller goat breeds may need less space.

Adapted from Canadian Agri-Food Research Council (CARC) (2003) Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals – Goats. Available at: https://www.nfacc.ca/pdfs/codes/goat_code_of_practice.pdf, Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (2010) Minimum Specification for Goat Housing. Available at: www.assets.gov.ie/95220/7d55e060-baf8-428b-b5e8-e3a6cfe419f3.pdf, New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (n.d.) Artificial methods of rearing goats. Available at: www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/animals-and-livestock/goats/mgt/rearing, and Vas J., Chojnacki R., Kjøren M.F., Lyngwa C. & Andersen I.L. (2013) Social interactions, cortisol and reproductive success of domestic goats (Capra hircus) subjected to different animal densities during pregnancy. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 147(1–2):117–126.

REQUIREMENTSGoats must be housed in groups and have enough space to turn around, lie down, stretch out when lying down, get up, rest, and groom themselves comfortably at all ages and stages of production (44). If overcrowding behaviours are observed, action must be promptly taken to reduce stocking density. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- increase space for goats in late gestation

- increase space for goats in warm weather

- increase space for goats with horns

- increase space for goats in pens when bucks are present for active breeding

- increase space allowances by:

• extending pen space

• moving goats

• reducing group size

• providing raised platforms.

2.3 Flooring

Goats prefer to walk on hard surfaces. Hard surfaces allow for natural wear of the hoof wall and may help promote hoof health. Goats may choose to lay on hard, dry surfaces like metal, wood, or rubber mattresses while they use areas bedded with shavings and straw for urination and defecation (45, 46). For this reason, providing both a bedded area and a hard, dry surface may be beneficial.

Flooring of bedded pens can be dirt or gravel, wood, rubber, plastic, or concrete. Bedding materials should be safe, non-toxic, and able to absorb moisture. There are typical welfare issues associated with different types of flooring.

Wood and earthen floors, if wet or muddy, create ideal conditions for foot rot and flies. Drainage, diverting rainwater, combined with bedding management can mitigate wetness. Dry lots should be well-drained. Inside earth/gravel floors should be set-up so drainage can occur (e.g., on grade, use of drainage tiles, correct materials).

Concrete floors, if designed to drain well, can be easily cleaned and sanitized. Newborn kids born on bare concrete can slip and are prone to splayed leg injuries. These floors also tend to be cold and damp. Good bedding management can overcome these issues.

Slatted floor nurseries (e.g., renovated pig barns) need to be kept warmer. For optimum kid health, floors need to be clean, with no drafts from below. The primarily milk diet, high urine production, higher temperatures, and lower amounts of bedding all promote the production of ammonia gases. Good hygiene and ventilation are imperative for raising healthy kids on slatted floors.

Refer to Section 2.8 – Bedding and Manure Management for more information.

REQUIREMENTSFlooring must be designed and maintained to minimize slipping and injury (11). Slatted floors must be maintained to prevent goats from becoming damp, cold, injured, or entrapped; drafts and ammonia levels must be minimized to reduce adverse health effects. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- choose flooring types that are non-slip but not overly abrasive (47, 48)

- locate sheds and other structures with earthen floors on well-drained sites or where runoff is diverted away from goat housing.

2.4 Feeder Design

Design feeders and feeding systems so that all goats can easily obtain feed comfortably and at the same time, especially when limit feeding a ration. Feeding space should be adjusted as youngstock grow, pregnancies progress, and for varying sizes across breeds and body types. Large-framed breeds, pregnant goats, and goats with horns may all require more physical space at feeders—up to double the space compared to hornless, dry goats (33).

It is very important to observe goats while feeding, note aggression or overcrowding behaviours, and increase feeding spaces accordingly. This may include installing new feeders, adding portable or temporary feeders or feed stations to pens, moving goats to different pens or pastures, or providing trays, buckets, or meals for individual timid goats.

Decreased feeder space per goat can lead to lower-ranking animals being forced to share feeding spaces or being prevented from feeding as higher-ranking animals take up multiple feeding spaces (49). For lower-ranking goats, this can lead to decreased time spent feeding, less frequent feeding, and more time waiting to feed (50).

Forage fed free choice in bale feeders and racks will need about half the feeder space. When feeding a total mixed ration, grain ration, or when top-dressing a ration, increase bunk space or reduce the number of goats in the pen until all goats can access feed at the same time. It is critical to get higher feed intake in the last trimester of pregnancy. Bucks in breeding pens may disrupt doe feed intake and take up multiple feeding spaces.

Feeding systems that are easy to clean and discourage fecal contamination make it easier and more likely to provide safe, clean, and palatable feed. Goats will have higher feed intake and better health when feeders are kept clean.

Table 2.2 – Minimum Feeder Space per Goat

Type of goat | Limit Feeding (feeding space width)* | |

cm / goat | inch / goat | |

Small does: 45 kg (100 lb) | 30 | 12 |

Average size does: 45–68 kg (100–150 lb) or Angoras in full fleece: 36–45 kg (80–100 lb) | 35–45 | 14–18 |

Larger does/Meat goats: 68–90 kg (150–200 lb) | 40–50 | 16–20 |

Horned goats Heavily pregnant & late gestation does | Feeding space per doe should be doubled | |

Bucks: 90–135 kg (150–300 lb) | 40–60 | 16–24 |

*The amount of feed space required is dependent on the size of goat, presence of horns, type of feed, and the feeding methods.

Adapted from Goat Code of Practice Scientific Committee (2020) Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Goats: Review of Scientific Research on Priority Issues. Lacombe, AB: National Farm Animal Care Council.

REQUIREMENTSLimit-fed goats must all be able to access feed at the same time. Feeders must be designed and maintained to prevent goats from becoming injured or accidentally entrapped. Feeders must be cleaned when contamination (e.g., feces, spoiled feed) is observed in the feeders. Feeders must be checked daily. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- allow additional feeder space (up to double) for pregnant does, especially at late stages of gestation

- monitor the herd and increase feeder space per goat if there is queuing at the feeder

- using dividers in the feeder will prevent goats from jostling and pushing each other at feeders and reduce aggression

- using raised feeder designs will allow goats to express their natural instinct to reach up and out to eat (52)

- elevate mangers 25–30 cm (10–12") above the floor or curb level

- accommodate the increasing depth of manure pack when setting feeder height

- design and manage feeders to prevent contamination of feed with manure, urine, or spoiled feed

- set large bales into bale feeders to avoid crushing/smothering injuries from bale collapse.

2.5 Watering Systems

Goats are very selective about the water they drink. Snow and ice are not suitable sole sources of water for goats. Electrically heated pails and water trough de-icing or heating devices, if not operating correctly, can shock goats as they drink, thus limiting their water consumption. Electrical panels must be checked to ensure that devices are properly grounded.

Waterers may cause a wet environment (e.g., leak or overflow), with more potential for flies, bacteria, and disease. Deep water troughs and 20 L (5 gal) pails of water are a drowning hazard to smaller goats. Waterers should be secured so they cannot be tipped.

Walking far distances to find water consumes energy, which is a greater consideration in very cold and very hot or dry weather. Goats on lush pasture may only drink 1–2 times per day, but on dryer forage, goats will need to drink more often. Refer to Section 4.7 – Drinking Water.

REQUIREMENTSWatering systems must be monitored daily to ensure that safe, clean, and palatable water is always available. Waterers must be designed and positioned to minimize contamination (e.g., fecal matter, feed). Waterers must be cleaned whenever contaminated (e.g., algae, organic material). All electrical watering devices must be properly grounded and maintained to prevent shocks. Waterers accessible by kids must be sized, positioned, and protected to prevent drowning. Producers must have a plan to supply water in an emergency (i.e., power failure, drought). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- encourage water intake using warm water, especially for lactating dairy goats. 15°C (59°F) is ideal (53)

- use warmer water rather than cold water when goats are experiencing heat stress

- waterers should be scrubbed weekly, at a minimum

- test well water and surface water used for drinking at least annually for indictors of water quality (53)

- access to surface water in pastures should not cause erosion or reduce water quality. It may be against local regulations to allow livestock to access surface water

- ensure that on pastures, water is within 0.8 km (½ mile) of grazing areas (53)

- limit depth of water for tanks and troughs used by kids to 20 cm (8"; 53).

2.6 Handling Systems

Goats do not flow through a handling system as smoothly as cattle and sheep and tend to rush toward an actual or expected opening. Goats readily drop to the ground under crowding pressure and are at greater risk from trampling and smothering.

For larger herds and difficult jobs, a good handling system contributes to lowering both animal and human stress. While a handling system is not always feasible or necessary, developing a process for handling will considerably help to manage stress.

Goats should be handled quietly. Goats will startle at sudden, loud, or unfamiliar sounds (e.g., air compressors or metal gates slamming). Excess noise creates agitation.

Longer chutes tend to cause crowding and trampling at the forward end and should be divided into sections with stop gates. An adjustable chute will allow for the handling of small goats and kids through to large bucks and goats with horns. The sides of the chute should be smooth and solid to prevent climbing and to encourage forward movement.

REQUIREMENTSHandling equipment or method of restraint must not cause injury or unnecessary stress to goats. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that handling systems are suitable for goats

- use a chute with solid sides to contribute to easier movement and prevent entrapment of horned goats

- walk the route and look for things that may cause distractions or balking before moving goats

- provide sufficient area and a clear, well-lit path for goats to move in desired directions

- ensure equipment is designed to minimize noise.

2.7 Enrichment

Goats need to be kept busy, as boredom is a welfare concern. Enrichments that are safe for goats, such as brushes, platforms, opportunities for climbing and hiding, and brush or trees offer amendments to housing and allow goats to perform their natural behaviours.

Providing enrichment can have long-term benefits such as reducing stress and aggression when exposed to changes in routine (such as handling or transport). Providing enrichment may also increase growth rates (54).

Does like to hide their newborn kids, and young kids will hide in small, safe enclosed spaces and corners (55).

REQUIREMENTSProvide goats with at least one form of enrichment. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- provide more than one form of enrichment for goats.

2.8 Bedding and Manure Management

Safe and dry bedding added consistently will keep animals comfortable and dry.

All goat housing areas, regardless of system, should be well drained to avoid wet conditions that can create welfare and health challenges (e.g., foot diseases, flies). Bedding provides warmth, insulation, and comfort for goats. In bedded pack systems, it is important to add fresh bedding material as necessary to keep bedding clean and dry, especially during kidding.

Manure and waste present a risk for spread of disease. For example, Johne’s disease and coccidiosis are spread through fecal-oral contact. Infectious abortion diseases are shed in birth fluids at kidding time and for up to 2 weeks after kidding. Waste may be an attractant for flies, scavengers, predators, and pests.

As a guide, bedding is too wet if one’s knees feel wet after 25 seconds of kneeling in the area. Goats look visibly dirty when bedding is insufficient and/or the pen environment is too wet (56).

REQUIREMENTSBedding must be provided in all buildings housing goats (except systems using slatted floors) to create a clean, comfortable, and dry surface. In cold temperatures, extra bedding must be provided. Manure and waste must be stored in a manner to:

|

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- avoid using sawdust bedding

- do not use spoiled hay in pens for bedding (associated with increased risk of listeriosis)

- observe the legs of goats over pressure points for signs of abrasions, swelling, or sores indicating inadequate bedding management

- add clean, dry bedding to maintain a dry, comfortable surface for goats (especially for bedded-pack pens)

- if bedding is too wet, check reason (e.g., leaky watering devices), and address promptly

- establish a protocol or written standard operating procedure (SOP) for waste removal.

2.9 Outdoor Facilities – Grazing and Pasturing

2.9.1 Fencing

Secure and robust fencing limits injury or escape. No single fence design is suitable for all landscapes, site conditions, or containment requirements (57).

Goats confined in smaller enclosures are more likely to investigate and damage fencing (58). Goats naturally want to stand on, or climb over, fences, creating sagging gaps and pressing fences outward. Horned goats can easily become entrapped in page wire fencing. It is very important to monitor fences every day and to release entrapped goats promptly.

Escaped goats usually do not stray far from their herds, although they become more vulnerable to predators.

Table 2.3 – Types of Fencing for Goats

Type of Fencing | Ideal Dimensions | Advantages | Disadvantages / Challenges |

Ideal: Woven or Field fence combined with electric fence

Board fence combined with electric fence | Strand of electric wire placed on inside of fence at nose height; and to prevent jumping (e.g., 1 or 2 strands 25cm [10"] above top of fence). | Offers more security than either fencing method on its own. Can safely utilize existing page wire fencing of most gauges. Electric wire prevents rubbing, damage to fence, and animals from becoming trapped or injured. | Goats can ingest toxins from treated wood or lead-based paint in board fence. Same challenges as electric fence below. |

Woven fence Page wire Field Fence | Ideal fence gauge varies with goat size and horn status. Adapt management and monitoring to existing fence. | Good for disbudded goats. Sheep fence has extra horizontal wires in lower 8–12" to prevent escapes. | Horned goats may get their head stuck in openings near posts, or in sagging and enlarged openings. |

Electric fence | Live wires should be minimum of 6–8" apart, including a horizontal wire placed ~ 6" from the ground to prevent goats from slipping through fence—may need up to 7 strands. | Higher voltage (4000–5000 volts) using a pulsing current will not damage a goat or predator but will leaves a lasting impression. | Long hair or fibre insulates the goat from feeling the charge. The fence needs to be checked daily for charge and to detect items that may be grounding the fence (e.g., weeds, fallen rails). Requires a source of electricity the entire time goats are in the pasture. Need to train goats to electric charge. |

Temporary electric netting | 1.1m (4 ft) height | Quick and easy way to set up temporary paddocks or fence off areas for a short term.

| See electric fence above. Horned goats can get snagged or entangled in netting. Need to train goats and monitor as with electric fencing. |

Stock fencing or hog panels (vertical steel rods welded) | 1.1m (4ft) height is usually adequate. To contain bucks—ideal height is ≥1.5m (5–6ft). | Goats are unlikely to get feet caught when standing on fence. | Welds can break when goats push/butt heads. Need to repair gaps and protruding rods. |

Chain-link fencing | 3–4" openings. | Small weave is most secure. | Small feet can get stuck. |

Use with Caution | Disadvantages | ||

Page wire fence for cattle (e.g., 8" x 12" holes) with no secondary electric fencing. | Horned goats get heads stuck. Young kids can escape through bottom. | ||

Picket fence Skids or pallets used as fencing | Broken legs, strangling. | ||

Barbed wire | Entangled goats become injured and highly stressed. Thin skin of goats can tear easily, causing severe damage including lacerated skin and udders. | ||

Sources: Belanger J. & Bredesen S.T. (2018) Storey's Guide to Raising Dairy Goats, 5th Edition: Breed Selection, Feeding, Fencing, Health Care, Dairying, Marketing. Storey Publishing. Ontario Goat (2014) Best Management Practices for Commercial Goat Production. Guelph ON: Ontario Goat.

REQUIREMENTSThere must be no sharp edges or protrusions (e.g., tail-end of the barbed wire) in fencing or in pasture that could injure goats. Fencing must be monitored daily for entrapped goats and corrective action taken as needed. If entrapment or injury is a recurring problem, stockpeople must investigate and repair. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- inspect all fences at least monthly (and repair if necessary). Additional inspections may be necessary immediately after a wind storm, snow blizzard, heavy blowing snow, or after escaped animals have returned (57). Additional inspections may be necessary for electric fencing

- check fences to ensure that they are firm and upright and that tension is being maintained (53)

- ensure that fencing is low to the ground to prevent animals from escaping, but tall enough to prevent predators from entering or goats from jumping out

- test electric fences for proper voltage and grounding and clear scrub and weeds from around the electrified strands (53)

- ensure that all perimeter gates have secure mechanisms to prevent accidental opening (e.g., latches, hooks, chains).

2.10 Milking Parlours

Most dairy goats are milked in a parlour although in smaller operations goats may be milked in a headstall. The parlour needs to be well designed so that the animals are not stressed or injured at milking time and move easily in and out. Good parlour design will also aid in complete, fast, and stress-free milk out (59). Most design layouts have 2 components: the milking parlour and the holding area.

The holding area is next to the parlour and holds groups so that milking can be done with a continual flow. A good design will make it easy for the animals to see where they are going (i.e., the parlour). No slope, or a steady low slope, will reduce stress when goats enter and leave the parlour. A space allowance of 0.325 m2 (3.5 ft2) is used as the goats are crowded only for a short time. A safe backing gate can be used to bring in the latecomers.

The milking parlour, which may vary widely in design, needs to be safe and not stressful for the animal. The floor should be smooth enough to be easy to clean, but with enough gripping surface so as not to be slippery. The headlock (if used), panels separating the goats during milking, and milking units should be adjusted so as not to injure any animals. Feeding in the parlour is optional and contributes to keeping the goat occupied, although may not be ideal for nutritional health. It is important to keep these working areas well illuminated (60).

Parlours should be easy to maintain and keep clean to safeguard animal health (by reducing potential for udder infections). Traffic through a parlour will inevitably cause a build-up of manure, urine, spilled milk, teat dip, and feed. It is critical for udder health that the parlour be set up for routine cleaning and sanitizing. It will also prevent a build-up of flies which cause mastitis and other diseases (55). Refer to Section 5.10.2 – Milking Procedures.

REQUIREMENTSParlour areas must be free of protrusions or sharp edges that could injure goats. Pens, ramps, milking parlours, and milking machines must be suitable for goats and be inspected and maintained to prevent injury, disease, and distress. Gates and restraining devices of milking stalls must operate smoothly and safely. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that milking parlours and holding areas are free of steep slopes (i.e., no more than 35°; 3)

- ensure that floors provide good traction to prevent slipping, even when wet

- ensure that parlour areas are well illuminated and ventilated

- goats should not be held in holding areas longer than 30 minutes

- use fans or other technology to moderate temperature extremes and eliminate condensation in milking parlours and holding areas.

3. Emergency Preparedness and Management

Desired Outcome: To safeguard goat welfare by minimizing threats from barn fires, power or mechanical failures, extreme weather, and natural disasters.

3.1 Emergency Prevention and Preparedness

Emergencies may arise and compromise goat welfare due to power failures, barn fires, wildfires, flooding, disruption of supplies, etc.

Emergencies are, by their nature, atypical and undesirable. They interrupt normal routines and can be quite devastating. It is normal, therefore, to avoid thinking about them, let alone planning for such. Advanced meaningful planning may help to prevent bad situations from becoming much worse.

Pre-planning (e.g., predicting, planning, and preventing) may enable producers to prevent emergencies and to respond in a timely and effective manner, thus providing for the welfare of goats during emergencies. Once methods to prevent emergency situations have been put in place and preparation for different types of emergencies has been completed, action plans must be established in case emergencies arise.

Emergency planning begins with the recognition that emergencies create stress, and that stress makes it harder to think clearly and act rationally. For this reason, effective emergency planning should strive to be as clear and as actionable as possible. While no two farm plans will be identical, there are common elements or steps that should be addressed (e.g., refer to Appendix B – Emergency Telephone List and Appendix C – Mapping Barns and Surrounding Areas for Fire Services). For most, if not all emergencies, the steps to be followed in terms of planning and responding are similar.

Do not assume that everyone knows what to do in the case of emergencies—this may not be the case. Make sure that everyone around the farm, including family members, knows what to do and that they have practiced different emergency plans—at least once. Practicing emergency scenarios is important to ensure that people respond calmly and automatically in possibly panic-inducing situations.

REQUIREMENTSAn emergency telephone list must be readily available for the producer, stockpeople, and emergency crews. Refer to Appendix B– Emergency Telephone List. Farm-specific procedures must be prepared for emergencies such as fires, equipment or power failures, and extreme weather events. The procedures must be written and communicated to stockpeople and family members. A map of the barn and its surroundings must be drawn and kept readily accessible for emergency crews. Refer to Appendix C – Mapping Barns and Surrounding Areas for Fire Services. Emergency plans must include specific actions and those designated to conduct specific actions. Plans must be easily accessible at the onset of an emergency. Plans must ensure that the welfare of the animals is maintained in any potential emergency event. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that stockpeople and family member training includes an annual review of the emergency procedures

- consider emergency management protocols when designing or renovating facilities (e.g., rapid evacuation of livestock, installation of fire alarms, emergency lighting)

- decide how and where animals will be relocated if necessary. Refer to Section 3.1.4 – Deciding to Evacuate or to Shelter in Place).

3.1.1 Fire in Farm Buildings

Fires in farm buildings are devastating events. The loss of animals, buildings, and equipment can be overwhelming. Approximately 40% of all barn fires are caused by faulty electrical systems, making it one of the leading causes of barn fires (62). Regular inspections and maintenance are key to reducing the risk of barn fires.

REQUIREMENTSAll electrical connections to equipment must be hard-wired. Extension cords must only be used temporarily and unplugged when not in use. All electric wiring, outlets, and fixtures (e.g., heat lamps) must be out of reach of livestock. Fire extinguishers must be available and maintained according to manufacturer’s instructions. Stockpeople must know where they are located and must be competent in their use. When in use, heat lamps and infra-red heaters must be kept at a safe distance from combustible materials, including bedding. Heat lamps must have a guard and must be suspended using non-combustible materials (62). |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- ensure that a fire safety self-assessment is completed annually. Refer to Appendix D – Assessing Farm Buildings for Fire Prevention

- consult local fire services for specific advice on fire prevention, including the correct number of and best location for fire extinguishers

- inspect and maintain electrical systems on a regular basis

- smoking, using torches, or other ignition sources (e.g., devices for disbudding kids), should not be allowed near any flammable materials

- refuel engines outside of barns, and only once they have been turned off and cooled down

- vent and provide a fresh air supply where grain handling and feed preparation activities generate dust

- properly protect electrical fixtures using conduit fittings and NEMA 4X

- use of totally enclosed fan-cooled motors is recommended

- remove combustible materials from around electrical systems and farm buildings to prevent build-up

- store flammable compounds in separate areas/buildings that are suitable for combustible materials and away from animal housing

- harvest and store hay properly to lower risk of spontaneous combustion

- store only a small amount of hay near animal housing

- only heat lamps or infra-red heaters with the CSA or ULC labels should be used.

3.1.2 Wildfires

A wildfire involves the uncontrolled burning of grasslands, brush, or woodlands. Wildfires destroy property and valuable natural resources and may threaten the lives of people and animals.

Wildfires can occur at any time of year, but usually occur during dry, hot weather. Check federal and provincial government websites for wildfire probability forecasts (e.g., Environment Canada). Local radio and television stations also broadcast information and warnings on local fire conditions.

Wildfires are normally recognized by dense smoke, which may fill the air over a large area. When a wildfire occurs, the decision to shelter in place, evacuate animals, and/or evacuate people must be continually considered as the situation evolves. Refer to Section 3.1.4 – Deciding to Evacuate or to Shelter in Place.

There are several actions that can be taken to prevent or reduce wildfires. The first is to reduce the risk of starting a fire in your own backyard. Refer to Section 3.1.1 – Fire in Farm Buildings, for guidance.

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- use only fire-resistant materials on the exterior of your barn or home, including the roof, siding, decking, and trim

- consider installing fire suppression systems for buildings as well as an outdoor system

- when constructing pools and ponds, make them accessible to fire equipment—they may serve as a source of water for fighting wildfires

- ensure that dedicated hoses are long enough to reach all parts of your building

- maintain a fire break around the perimeter of the property, pastures, or buildings

- controlled burns should not be conducted near livestock buildings. Local fire departments should be consulted for advice on controlled burns.

3.1.3 Power/Mechanical Failure

Power and mechanical failures may trigger on-farm emergencies capable of endangering animals and their caretakers. These failures have a greater impact on goats that are reliant on power and mechanics to provide feed, water, ventilation, and milking.

REQUIREMENTSIf the systems cannot be run manually, an alternative method or power source must be available to run critical systems (e.g., watering system, ventilation, milking, feeding). Producers must have enough feed and safe, clean, and palatable water to meet the needs of their goats for at least 72 hours. All electrical and mechanical equipment and services including water bowls and troughs, ventilating fans, heating and lighting units, milking machines, and alarm systems must be inspected at least annually and kept in good working order. |

RECOMMENDED PRACTICES

- calculate the amount of water that your goats need daily. A reliable backup source of water of acceptable quality should be identified. This can be a well if a generator is available to operate a pump

- estimate the electrical needs of your farm to ensure production and management continuance

- a generator (fuel or tractor powered) should be available for emergency use

- keep fuel reserves sufficient to run the generator for 72 hours on-site

- alarms and fail-safe devices, including an on-farm alternate power supply, should be tested according to manufacturer’s recommendations to ensure that they are in working order

- a standard operating procedure for maintenance of all equipment and services on-farm should be developed and available for stockpeople

- determine the minimum daily feed ration for the goats’ level of production. Consult with your nutritionist or supplier to establish these minimums

- keep extra maintenance supplies and parts on hand in case of longer delivery times due to adverse weather conditions or road closures in your area.

3.1.4 Deciding to Evacuate or to Shelter in Place

In times of extreme environmental conditions, and if thorough preparations are in place (including a good emergency plan that can be implemented if or when needed), staying on-farm may be conceivable. However, in emergency situations involving flooding or wildfires, the evacuation of animals and/or humans may be necessary. To help prepare for proper evacuation planning of animals and family, consider the following:

- contact local emergency management authorities to become familiar with at least 2 possible evacuation routes

- arrange for a place to shelter animals (e.g., fairgrounds, other farms, racetracks, exhibition centres). Accommodations will need to include milking equipment for dairy goats (as applicable)

- consider the health status of the herd and whether they will come into contact with other herds during evacuation

- ensure that enough feed, water, and medical supplies are available at the destination

- consider how animals and people will be safely transported

- make sure animals have enough identification (e.g., ear tags or leg bands) to be able to tell them apart from others

- make sure to have adequate and safe fencing or pens to separate and group animals appropriately

- prepare an emergency kit that will follow the animals (refer to Appendix E – To Prepare in Case of Evacuation).

There may be circumstances where the risk to life is great and there is not enough time to evacuate animals (e.g., having a wildfire start in the immediate area). In this situation:

- protection of human life and safety should be the priority

- after ensuring human safety and if it is safe to do so and time permits:

- open gates between pens and pastures to give the animals more room to escape the hazard. Do not to let animals out into unfenced areas as they could become hazards on roads or for emergency rescue teams

- put extra feed and water out where the animals can get to it, as it may be a few days before caretakers are allowed to return home

- consider turning off power, propane, and natural gas to reduce the chance of these utilities causing additional problems.